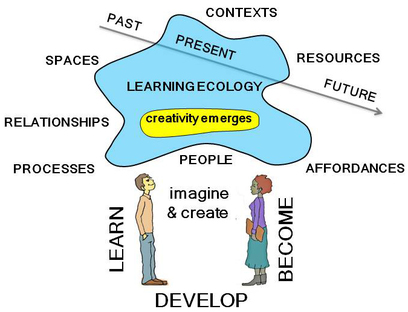

Lifewide Education and Creative Academic are exploring the idea of learning ecologies and we have shared initial ideas in a book 'Exploring Learning Ecologies'. In the book I touch on the idea that ecologies for learning development and achievement are also the vehicles for our creativity. Creativity is not separate from the things we want to achieve and from the ongoing development of ourselves as the person we want to become. Chrissi Nerantzi and I had the idea of forming a conversation around the idea of creative ecologies on the #creativeHE platform so for 7 days in early July about 20 people came together in the #creativeHE space to share their thoughts. https://plus.google.com/communities/110898703741307769041

It was an interesting thought provoking conversation. Much of it was about exploring perceptions of creativity rather than the idea of creative ecologies. This was necessary in order to try to create a foundation of shared perceptions on which to base discussion. We all take away different things from a conversation - which is another way of saying that our unique complexity sees different value in the meanings that are shared. I will just pull out a few perspectives that caused me to progress my own understanding.

The struggles to comprehend and create meaning was one of the most creative aspects of the conversation and there were many illustrations of what a creative ecology might mean. They are all valid if the person who invented them feels that it embodies and represents their creative experiences and self-expression. This open sharing of personally constructed meanings is a sign of a healthy conversation. But it takes confidence and courage to publicly share ideas, thoughts and feelings, and the meanings you have created in the #creativeHE space and I suspect that many participants monitor the conversation but do not post because of this. I hope through our consistent behaviour in the #creativeHE conversational space we are creating a culture of encouragement, trust and respect whereby most people feel empowered to contribute. At the end of the day each individual must make their own meanings and assimilate them into their own framework of knowledge and understanding. Here are a few new perspectives I gained from the conversation

It was an interesting thought provoking conversation. Much of it was about exploring perceptions of creativity rather than the idea of creative ecologies. This was necessary in order to try to create a foundation of shared perceptions on which to base discussion. We all take away different things from a conversation - which is another way of saying that our unique complexity sees different value in the meanings that are shared. I will just pull out a few perspectives that caused me to progress my own understanding.

The struggles to comprehend and create meaning was one of the most creative aspects of the conversation and there were many illustrations of what a creative ecology might mean. They are all valid if the person who invented them feels that it embodies and represents their creative experiences and self-expression. This open sharing of personally constructed meanings is a sign of a healthy conversation. But it takes confidence and courage to publicly share ideas, thoughts and feelings, and the meanings you have created in the #creativeHE space and I suspect that many participants monitor the conversation but do not post because of this. I hope through our consistent behaviour in the #creativeHE conversational space we are creating a culture of encouragement, trust and respect whereby most people feel empowered to contribute. At the end of the day each individual must make their own meanings and assimilate them into their own framework of knowledge and understanding. Here are a few new perspectives I gained from the conversation

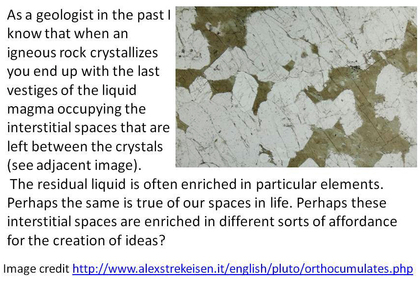

Interstitial spaces - are not always inconsequential spaces for learning

Jonathan Purdy talked about how Different spaces afford me different things. They alter my mind set. In my garage I'm looking to use something old, often something with its own history that will live on in whatever I create with it and that I will get satisfaction from using up. In the store I'm being afforded the solutions to problems that others have designed, and I sometimes have to re-cast my problem to fit their solution. And in the drawing space - well, anything goes! Similarly Andrew Middleton also talked about spaces particularly informal and non-formal spaces and the creation of a map showing the diversity of spaces/places that a group of people attending his workshop believed they learnt.

In my representations of learning ecologies I pay attention to the big obvious spaces but not so much the little ones. The reality is our life is full of little spaces often transitional between bigger seemingly more important spaces Andrew Middleton's idea of interstitial spaces struck me as being important to an ecological perspective of learning.

Jonathan and Andrew's posts made me think of all the incidental and interstitial spaces and moments that flow through our ecologies for learning which help us connect up the dots of our imagination, critical thinking, reflective, associative and integrative (synthetic) thinking to make the whole of what it is we are trying to do and achieve. All these seemingly insignificant spaces offer us affordance to think. In particular they offer affordances for creativity because we may not be thinking in a conscious deliberative way about a problem or situation they provide us with affordance for the associative and synthetic types of thinking when ideas come into our head seemingly from nowhere.

So in future I will view the interstitial spaces in my learning ecologies with more respect and ask how did these spaces contribute to my learning. In this ecology my interstitial spaces were restricted as I'm mainly around the house recovering from a knee operation, so they are mainly in my garden eg chatting to my son Navid as we cut the hedge and chatting in the kitchen over lunch. Both of these homely interstitial spaces were important in this ecology.

Jonathan Purdy talked about how Different spaces afford me different things. They alter my mind set. In my garage I'm looking to use something old, often something with its own history that will live on in whatever I create with it and that I will get satisfaction from using up. In the store I'm being afforded the solutions to problems that others have designed, and I sometimes have to re-cast my problem to fit their solution. And in the drawing space - well, anything goes! Similarly Andrew Middleton also talked about spaces particularly informal and non-formal spaces and the creation of a map showing the diversity of spaces/places that a group of people attending his workshop believed they learnt.

In my representations of learning ecologies I pay attention to the big obvious spaces but not so much the little ones. The reality is our life is full of little spaces often transitional between bigger seemingly more important spaces Andrew Middleton's idea of interstitial spaces struck me as being important to an ecological perspective of learning.

Jonathan and Andrew's posts made me think of all the incidental and interstitial spaces and moments that flow through our ecologies for learning which help us connect up the dots of our imagination, critical thinking, reflective, associative and integrative (synthetic) thinking to make the whole of what it is we are trying to do and achieve. All these seemingly insignificant spaces offer us affordance to think. In particular they offer affordances for creativity because we may not be thinking in a conscious deliberative way about a problem or situation they provide us with affordance for the associative and synthetic types of thinking when ideas come into our head seemingly from nowhere.

So in future I will view the interstitial spaces in my learning ecologies with more respect and ask how did these spaces contribute to my learning. In this ecology my interstitial spaces were restricted as I'm mainly around the house recovering from a knee operation, so they are mainly in my garden eg chatting to my son Navid as we cut the hedge and chatting in the kitchen over lunch. Both of these homely interstitial spaces were important in this ecology.

Creativity and synthesis

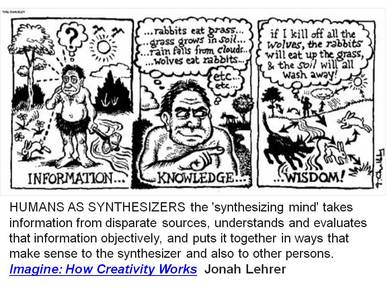

Navid Tomlinson made an interesting point that in his view people are 'human synthesizers, we are all continuously taking little bits of information and combining them in different ways to create different outputs, outputs which can be anything from the way we conduct ourselves in conversation to books we may write or even the way we play games. Under this definition we are all being continuously creative but to differing levels of complexity.'

Figure Humorous depiction of the way we integrate and synthesize lots of observations and information to create new understandings.

This suggests that at the heart of our learning ecology is a synthesizing process through which we create new meaning. I like the idea that our creativity reflects the fact that we all have the innate capacity to be inspired and take information in through all our senses, across all the different parts of our life, and throughout our whole life span. We are able to filter and make use of this information at particular times, either by accident or design, by connecting and combining it with other thoughts to create new thoughts and feelings that mean something to us.

I realise that I try to do this all the time and perhaps it is the main creative process for most academics. When I am interested in something I put lots of time and energy into thinking about it. I take lots of information and ideas and try to connect them to ideas and beliefs I already hold in ways that make sense to me to make a more complex understanding that I try to apply and justify. It happened with the ideas of lifewide learning and learning ecologies and my attempt to embed the idea of creativity within the affordance provided by a learning ecology is another example that we have been grappling with. Going back to my days as a geologist I engaged in synthesis all the time in my research and practice as a field geologist - making a map is a way of synthesising and presenting geological information and creating a mediating artefact. I suspect that the tendency to synthesise is programmed into us so that we can transfer the tendency from one domain or context to another.

I think this perspective freshens and reinforces a belief I already hold about my learning ecology. At the heart of my learning ecology is the seek (information) sense (filter, process, create meaning from information), share (synthesised meanings) model that has been developed by Harold Jarche.

(Jarch 2014).

Irene Stella Vassilakopouou made the important point that although we may create and share the meanings we create through synthesis, 'the way we understand things doesn't [necessarily] make sense to others, so sometimes [the results of] our creativity may frustrate the other people.' Simply sharing the meanings we have created and share does not mean that someone else will accept these meaning in the same way. I read somewhere that once you have shared a meaning with an audience you no longer control it. It becomes whatever each person in the audience feels it means and this is the likely process within our conversation and the likely outcome of the conversation. Perhaps our creativity only becomes recognised when enough people in the field accept the meanings we have created

Navid Tomlinson made an interesting point that in his view people are 'human synthesizers, we are all continuously taking little bits of information and combining them in different ways to create different outputs, outputs which can be anything from the way we conduct ourselves in conversation to books we may write or even the way we play games. Under this definition we are all being continuously creative but to differing levels of complexity.'

Figure Humorous depiction of the way we integrate and synthesize lots of observations and information to create new understandings.

This suggests that at the heart of our learning ecology is a synthesizing process through which we create new meaning. I like the idea that our creativity reflects the fact that we all have the innate capacity to be inspired and take information in through all our senses, across all the different parts of our life, and throughout our whole life span. We are able to filter and make use of this information at particular times, either by accident or design, by connecting and combining it with other thoughts to create new thoughts and feelings that mean something to us.

I realise that I try to do this all the time and perhaps it is the main creative process for most academics. When I am interested in something I put lots of time and energy into thinking about it. I take lots of information and ideas and try to connect them to ideas and beliefs I already hold in ways that make sense to me to make a more complex understanding that I try to apply and justify. It happened with the ideas of lifewide learning and learning ecologies and my attempt to embed the idea of creativity within the affordance provided by a learning ecology is another example that we have been grappling with. Going back to my days as a geologist I engaged in synthesis all the time in my research and practice as a field geologist - making a map is a way of synthesising and presenting geological information and creating a mediating artefact. I suspect that the tendency to synthesise is programmed into us so that we can transfer the tendency from one domain or context to another.

I think this perspective freshens and reinforces a belief I already hold about my learning ecology. At the heart of my learning ecology is the seek (information) sense (filter, process, create meaning from information), share (synthesised meanings) model that has been developed by Harold Jarche.

(Jarch 2014).

Irene Stella Vassilakopouou made the important point that although we may create and share the meanings we create through synthesis, 'the way we understand things doesn't [necessarily] make sense to others, so sometimes [the results of] our creativity may frustrate the other people.' Simply sharing the meanings we have created and share does not mean that someone else will accept these meaning in the same way. I read somewhere that once you have shared a meaning with an audience you no longer control it. It becomes whatever each person in the audience feels it means and this is the likely process within our conversation and the likely outcome of the conversation. Perhaps our creativity only becomes recognised when enough people in the field accept the meanings we have created

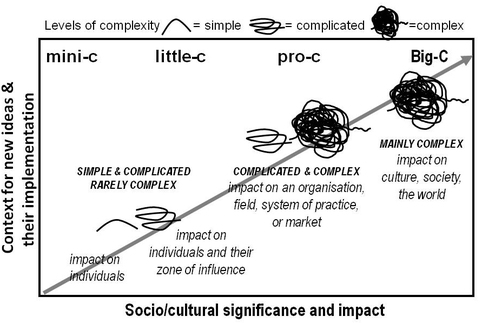

Creativity through synthesis with different levels of complexity

Navid Tomlinson argued that 'If creativity is simply creating something new then it cannot be more or less creative, creativity is an absolute'. In order to distinguish between creative acts he uses the idea of complexity. At the heart of his concept is the idea that creativity can be differentiated by the levels of complexity involved in the synthesis. [If] I have synthesised multiple sources, thought about and grappled with [multiple and]complex ideas, [I have] produced a complex product - my change in understanding. ...................It seems to be there is a direct correlation between the complexity of our ecology and the complexity of our creative products,

I would suggest that we should see complex ecologies as a method to help us produce complex creative outputs. Complexity may be reflected such things as the scale and scope of our learning ecology, the amount and level of knowledge and skill we need to develop the number and quality of relationships we need to form, the number of people who are directly involved who influence and co-create the ecology, the time scale over which the ecology is developed and its connectivity to other learning ecologies, the resources that we need to support it.

https://docs.google.com/document/d/1v6SpLGknfG0zRJ5KEat7LM3PFXp0FJUhBaN-u2L9Px8/edit

I thought there were a lot of interesting ideas in Navid's article so I sat down and wrote my own thoughts.

Complexity and people

We might begin by recognising that people themselves embody different levels of complexity in their personalities, behaviours, cognitive and imaginary abilities and psychologies. The social psychologist Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi studied the lives of 91 eminent creators, what he terms “big C” creatives who changed their domains, in search of what they might have in common. He concluded If I had to express in one word what makes their personalities different from others, it's complexity. They show tendencies of thought and action that in most people are segregated. They contain contradictory extremes; instead of being an "individual," each of them is a "multitude." (Csikszentmihalyi 1996).

By "complexity" he meant (Rivero 2015) having personalities of “contradictory extremes,” such as being both extremely smart and naïve, or traditional and rebellious, or objective and passionate. There is little middle ground. Creatively complex people are nearly impossible to “peg” as this or that. Their capacity to tap into a fuller range of what life has to offer is what allows them a broader response to life’s problems and questions, whether practical or artistic.

Complexity in situations, problems and opportunities

The human condition is to try to understand situations in order to make good decisions about how to act (or not to act). Some situations are easy to comprehend: they are familiar and we have dealt with them or something like them before and we are confident that we know what to do. Others are more difficult to understand and some are impossible to understand until we have engaged in them. Situations can be categorised according to whether the context is familiar or unfamiliar and whether the problem (challenge or opportunity) is familiar or unfamiliar. Unfamiliarity, is one aspect of complexity.

We might speculate that the increasing complexity of situations will demand increasingly complex learning ecologies to deal with them. We might also anticipate that highly complex situations and problems cannot be resolved by individuals but require teams of people working together over considerable periods of time. We might visualise different levels of complexity in social situations using the Cynefin framework developed by Snowden (Snowden 2000). There are four domains within the framework.

In the simple domain things have a simple cause and effect. Complicated situations are not single events but involve a stream of interconnected situations (many of which may be simple) linked to achieving a goal (like solving a difficult problem or bringing about a significant innovation or corporate performance). They can be difficult to understand: there cause-and-effect relationships might not be obvious but you have to put some effort into working out the relationships by gathering information about the situation and analysing it to see the patterns and look for possible explanations of what is happening. Engaging in these sorts of challenges is the way you become more expert in achieving difficult things and a lot of professional work is like this.

Complex situations are the most difficult to understand. They are not single events but involve multiple streams of variably connected situations linked to achieving a significant change in the pattern of beliefs and behaviours (culture) in a society or organisation. In such situations the cause-and-effect relationships are so intertwined that things only make sense in hindsight and sometimes well after the events have taken place. In the complex space, it’s all about the inter-connectivity of people and their evolving behaviours and patterns of participation that are being encouraged or nurtured through the actions of key agents. The results of action will be unique to the particular situation and cannot be directly repeated. In these situations relationships are not straightforward and things are unpredictable in detail.

Figure My own synthesis combining the 4C model of creativity Kaufman and Beghetto (2000) with the complexity model of Snowden (2000). An adaptive creative product of the conversation.

Levels of complexity in learning ecologies

In developing capability for dealing effectively with situations we are developing the ability to comprehend and appraise situations, and perform appropriately and effectively in situations of different levels of complexity. The idea of learning ecologies has been proposed to help explain the relationships of people to their environment / contexts /resources, their problems and perceived affordances and the pattern of interactions and outcomes, as people pursue learning and achievement goals (Jackson 2016). We might make use of the Cynefin tool to evaluate the situations, problems and opportunities our ecologies for learning and creativity are engaging with. I illustrated the idea with examples of simple, complicated and complex learning ecologies.

Kaufman and Beghetto (2000) suggest that human creativity can be categorised into'Big-C' creativity that brings about significant change in a domain; 'pro-c' creativity associated with the creative acts of experts or people who have mastered a field, including but not only people involved in professional activity; 'little-c' creativity - the everyday creative acts of individuals who are not particularly expert in a situation and 'mini-c' the novel and personally meaningful interpretation of experiences, actions and events made by individuals. I attempted my own synthesis to integrate a complexity perspective into the 4C model of creativity. We might speculate that little-c creativity involves relatively simple and complicated situations and problems pro-c creativity involves complicated and complex situations and Big-C creativity would be mainly concerned with situations and problems that are complex but would also subsume simple and complicated situations within complexity.

My new appreciation of the relationship between creativity, complexity and creative ecologies

Synthesis has been a recurrent theme in the #creativeHE conversation and my new understandings are of this nature. I like the idea that ultimately our motivation to be creative reflects both circumstances and affordances we perceive in our environment, our highly individual qualities and capabilities as a person and our intrinsic need or desire to do things for ourselves that help us become 'a newer [and better] version of oneself' (Paula Nottingham) in the manner Navid Tomlinson describes and Rogers (1961)equates with self-actualisation. I think it's this combination of a person interacting with themselves (their complexity) and their environment (affordance and complexity) that shapes the way a person's creativity emerges. It is not surprising to me that the combination of an individual's unique complexity (personality, orientations, passions and other emotions, capabilities, experiences/past history, values, beliefs and ambitions .....), perceiving an environment in which there are affordances - potential for acting in certain ways to achieve particular things, should choose to act in ways that leads to outcomes that the individual would believe were creative (in an absolute rather than qualitative way), if they held a concept of creativity that accommodated these outcomes. It does not mean that other people will perceive these outcomes as being creative as they may lack the knowledge to make a judgment and/or hold different understandings of what being creative means.

Looking back over the week I can see my own creativity in action in the way I played with and develop ideas that were shared and combined and synthesised them in real time with ideas I already owned. Once again I am reminded of two concepts of creativity that seem to explain what was happening in me as I interacted with my complex world with my unique complexities that make me who I am and who I want to become namely:

Creativity is 'the desire and ability to use imagination, insight, intellect, feeling and emotion to move an idea from one state to an alternative, previously unexplored state' (Dellas and Gaier's 1970)

'the emergence in action of a novel relational product growing out of the uniqueness of the individual on the one hand, and the materials, events, people, or circumstances of his/her life', (Rogers 1961/2004:350).

FOOTNOTE: Creative Academic Magazine #5 to be published in September will draw on the content of the July #creativeHE conversation.

Relevant sources

Csikszentmihalyi M (1996) Creativity: The Work and Lives of 91 Eminent People, by, published by

Dellas, M., & Gaier, E. L. (1970) Identification of creativity: The individual. Psychol. Bull. 73:55– 73

HarperCollins, 1996. https://www.psychologytoday.com/articles/199607/the-creative-personality

Jackson, N J (2016) Exploring Learning Ecologies Lulu publishing

Jarche, H. (2014) The Seek > Sense > Share Framework Inside Learning Technologies January 2014, Posted Monday, 10 February 22 014 http://jarche.com/2014/02/the-seek-sense-share-framework/

Kaufman, J.C., and Beghetto, R.A. (2009) Beyond Big and Little: The Four C Model of Creativity. Review of General Psychology 13, 1, 1-12.

Rivero L (2015) Creativity’s Monsters: Making Friends with Complexity Psychology Today

https://www.psychologytoday.com/blog/creative-synthesis/201502/creativity-s-monsters-making-friends-complexity

Rogers, C.R., (1961) On becoming a person. Boston: Houghton Mifflin

Snowden, D. (2000) Cynefin, A Sense of Time and Place: An Ecological Approach to Sense Making and Learning in Formal and Informal Communities. Conference proceedings of KMAC at the University of Aston, July 2000 and Snowden, D. (2000) Cynefin: A Sense of Time and Space, the Social Ecology of Knowledge Management. In C. Despres and D. Chauvel (eds)Knowledge Horizons: The Present and the Promise of Knowledge Management, Bost on: Butterworth Heinemann.

Stephenson, J. (1998) The Concept of Capability and Its Importance in Higher Education. In J. Stephenson and M. Yorke (eds) Capability and Quality in Higher Education, London: Kogan Page.

Tomlinson N (2016) Complex ecologies and creativity

https://docs.google.com/document/d/1v6SpLGknfG0zRJ5KEat7LM3PFXp0FJUhBaN-u2L9Px8/edit#

Norman Jackson

Founder Creative Academic

Navid Tomlinson argued that 'If creativity is simply creating something new then it cannot be more or less creative, creativity is an absolute'. In order to distinguish between creative acts he uses the idea of complexity. At the heart of his concept is the idea that creativity can be differentiated by the levels of complexity involved in the synthesis. [If] I have synthesised multiple sources, thought about and grappled with [multiple and]complex ideas, [I have] produced a complex product - my change in understanding. ...................It seems to be there is a direct correlation between the complexity of our ecology and the complexity of our creative products,

I would suggest that we should see complex ecologies as a method to help us produce complex creative outputs. Complexity may be reflected such things as the scale and scope of our learning ecology, the amount and level of knowledge and skill we need to develop the number and quality of relationships we need to form, the number of people who are directly involved who influence and co-create the ecology, the time scale over which the ecology is developed and its connectivity to other learning ecologies, the resources that we need to support it.

https://docs.google.com/document/d/1v6SpLGknfG0zRJ5KEat7LM3PFXp0FJUhBaN-u2L9Px8/edit

I thought there were a lot of interesting ideas in Navid's article so I sat down and wrote my own thoughts.

Complexity and people

We might begin by recognising that people themselves embody different levels of complexity in their personalities, behaviours, cognitive and imaginary abilities and psychologies. The social psychologist Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi studied the lives of 91 eminent creators, what he terms “big C” creatives who changed their domains, in search of what they might have in common. He concluded If I had to express in one word what makes their personalities different from others, it's complexity. They show tendencies of thought and action that in most people are segregated. They contain contradictory extremes; instead of being an "individual," each of them is a "multitude." (Csikszentmihalyi 1996).

By "complexity" he meant (Rivero 2015) having personalities of “contradictory extremes,” such as being both extremely smart and naïve, or traditional and rebellious, or objective and passionate. There is little middle ground. Creatively complex people are nearly impossible to “peg” as this or that. Their capacity to tap into a fuller range of what life has to offer is what allows them a broader response to life’s problems and questions, whether practical or artistic.

Complexity in situations, problems and opportunities

The human condition is to try to understand situations in order to make good decisions about how to act (or not to act). Some situations are easy to comprehend: they are familiar and we have dealt with them or something like them before and we are confident that we know what to do. Others are more difficult to understand and some are impossible to understand until we have engaged in them. Situations can be categorised according to whether the context is familiar or unfamiliar and whether the problem (challenge or opportunity) is familiar or unfamiliar. Unfamiliarity, is one aspect of complexity.

We might speculate that the increasing complexity of situations will demand increasingly complex learning ecologies to deal with them. We might also anticipate that highly complex situations and problems cannot be resolved by individuals but require teams of people working together over considerable periods of time. We might visualise different levels of complexity in social situations using the Cynefin framework developed by Snowden (Snowden 2000). There are four domains within the framework.

In the simple domain things have a simple cause and effect. Complicated situations are not single events but involve a stream of interconnected situations (many of which may be simple) linked to achieving a goal (like solving a difficult problem or bringing about a significant innovation or corporate performance). They can be difficult to understand: there cause-and-effect relationships might not be obvious but you have to put some effort into working out the relationships by gathering information about the situation and analysing it to see the patterns and look for possible explanations of what is happening. Engaging in these sorts of challenges is the way you become more expert in achieving difficult things and a lot of professional work is like this.

Complex situations are the most difficult to understand. They are not single events but involve multiple streams of variably connected situations linked to achieving a significant change in the pattern of beliefs and behaviours (culture) in a society or organisation. In such situations the cause-and-effect relationships are so intertwined that things only make sense in hindsight and sometimes well after the events have taken place. In the complex space, it’s all about the inter-connectivity of people and their evolving behaviours and patterns of participation that are being encouraged or nurtured through the actions of key agents. The results of action will be unique to the particular situation and cannot be directly repeated. In these situations relationships are not straightforward and things are unpredictable in detail.

Figure My own synthesis combining the 4C model of creativity Kaufman and Beghetto (2000) with the complexity model of Snowden (2000). An adaptive creative product of the conversation.

Levels of complexity in learning ecologies

In developing capability for dealing effectively with situations we are developing the ability to comprehend and appraise situations, and perform appropriately and effectively in situations of different levels of complexity. The idea of learning ecologies has been proposed to help explain the relationships of people to their environment / contexts /resources, their problems and perceived affordances and the pattern of interactions and outcomes, as people pursue learning and achievement goals (Jackson 2016). We might make use of the Cynefin tool to evaluate the situations, problems and opportunities our ecologies for learning and creativity are engaging with. I illustrated the idea with examples of simple, complicated and complex learning ecologies.

Kaufman and Beghetto (2000) suggest that human creativity can be categorised into'Big-C' creativity that brings about significant change in a domain; 'pro-c' creativity associated with the creative acts of experts or people who have mastered a field, including but not only people involved in professional activity; 'little-c' creativity - the everyday creative acts of individuals who are not particularly expert in a situation and 'mini-c' the novel and personally meaningful interpretation of experiences, actions and events made by individuals. I attempted my own synthesis to integrate a complexity perspective into the 4C model of creativity. We might speculate that little-c creativity involves relatively simple and complicated situations and problems pro-c creativity involves complicated and complex situations and Big-C creativity would be mainly concerned with situations and problems that are complex but would also subsume simple and complicated situations within complexity.

My new appreciation of the relationship between creativity, complexity and creative ecologies

Synthesis has been a recurrent theme in the #creativeHE conversation and my new understandings are of this nature. I like the idea that ultimately our motivation to be creative reflects both circumstances and affordances we perceive in our environment, our highly individual qualities and capabilities as a person and our intrinsic need or desire to do things for ourselves that help us become 'a newer [and better] version of oneself' (Paula Nottingham) in the manner Navid Tomlinson describes and Rogers (1961)equates with self-actualisation. I think it's this combination of a person interacting with themselves (their complexity) and their environment (affordance and complexity) that shapes the way a person's creativity emerges. It is not surprising to me that the combination of an individual's unique complexity (personality, orientations, passions and other emotions, capabilities, experiences/past history, values, beliefs and ambitions .....), perceiving an environment in which there are affordances - potential for acting in certain ways to achieve particular things, should choose to act in ways that leads to outcomes that the individual would believe were creative (in an absolute rather than qualitative way), if they held a concept of creativity that accommodated these outcomes. It does not mean that other people will perceive these outcomes as being creative as they may lack the knowledge to make a judgment and/or hold different understandings of what being creative means.

Looking back over the week I can see my own creativity in action in the way I played with and develop ideas that were shared and combined and synthesised them in real time with ideas I already owned. Once again I am reminded of two concepts of creativity that seem to explain what was happening in me as I interacted with my complex world with my unique complexities that make me who I am and who I want to become namely:

Creativity is 'the desire and ability to use imagination, insight, intellect, feeling and emotion to move an idea from one state to an alternative, previously unexplored state' (Dellas and Gaier's 1970)

'the emergence in action of a novel relational product growing out of the uniqueness of the individual on the one hand, and the materials, events, people, or circumstances of his/her life', (Rogers 1961/2004:350).

FOOTNOTE: Creative Academic Magazine #5 to be published in September will draw on the content of the July #creativeHE conversation.

Relevant sources

Csikszentmihalyi M (1996) Creativity: The Work and Lives of 91 Eminent People, by, published by

Dellas, M., & Gaier, E. L. (1970) Identification of creativity: The individual. Psychol. Bull. 73:55– 73

HarperCollins, 1996. https://www.psychologytoday.com/articles/199607/the-creative-personality

Jackson, N J (2016) Exploring Learning Ecologies Lulu publishing

Jarche, H. (2014) The Seek > Sense > Share Framework Inside Learning Technologies January 2014, Posted Monday, 10 February 22 014 http://jarche.com/2014/02/the-seek-sense-share-framework/

Kaufman, J.C., and Beghetto, R.A. (2009) Beyond Big and Little: The Four C Model of Creativity. Review of General Psychology 13, 1, 1-12.

Rivero L (2015) Creativity’s Monsters: Making Friends with Complexity Psychology Today

https://www.psychologytoday.com/blog/creative-synthesis/201502/creativity-s-monsters-making-friends-complexity

Rogers, C.R., (1961) On becoming a person. Boston: Houghton Mifflin

Snowden, D. (2000) Cynefin, A Sense of Time and Place: An Ecological Approach to Sense Making and Learning in Formal and Informal Communities. Conference proceedings of KMAC at the University of Aston, July 2000 and Snowden, D. (2000) Cynefin: A Sense of Time and Space, the Social Ecology of Knowledge Management. In C. Despres and D. Chauvel (eds)Knowledge Horizons: The Present and the Promise of Knowledge Management, Bost on: Butterworth Heinemann.

Stephenson, J. (1998) The Concept of Capability and Its Importance in Higher Education. In J. Stephenson and M. Yorke (eds) Capability and Quality in Higher Education, London: Kogan Page.

Tomlinson N (2016) Complex ecologies and creativity

https://docs.google.com/document/d/1v6SpLGknfG0zRJ5KEat7LM3PFXp0FJUhBaN-u2L9Px8/edit#

Norman Jackson

Founder Creative Academic

RSS Feed

RSS Feed