One of the challenges to understanding creativity is to comprehend it as a phenomenon that embraces the acts of individuals that have significance and meaning only to them, and the acts of creative giants who quite literally change the way we see and experience the world at a cultural or cross-cultural level. I believe that we will only progress our understanding if we can develop a perspective on creativity that accommodates and integrates both world views.

These different ways of thinking about creativity are captured in the thinking and writings of 1) Carl Rogers who approaches creativity from a humanist, person- and individual- centred therapeutic perspective and 2) Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi who approaches creativity through the lens of individuals acting in systems and cultures. Kristen Bettencourt (3) neatly captures the philosophies of these thinkers and these notes are taken from her article.

Rogers (1) defines the creative process as “the emergence in action of a novel relational product, growing out of the uniqueness of the individual on the one hand, and the materials, events, people, or circumstances on the other” (p. 251). Rogers points out, “the very essence of the creative is its novelty, and hence we have no standard by which to judge it” (p.252). Rogers leaves room in the definition of creativity for the creator to define whether the expression is indeed novel, going as far to say that anyone other than the creator cannot be a valid or accurate judge. This is in contrast to Csikszentmihalyi’s emphasis on the creative expression serving to transform the culture or the domain.

Csikszentmihalyi (2) “creativity does not happen inside people’s heads, but in the interaction between a person’s thoughts and sociocultural context. It is a systemic rather than individual phenomenon” (2 p.23). Csikszentmihalyi tells us “To be human means to be creative,” he defines creativity as “to bring into existence something genuinely new that is valued enough to be added to the culture” (2 p.25), and “any act, idea, or product that changes an existing domain, or that transforms an existing domain into a new one” (2 p.28). The word “creative” is given to expression seen as novel in relation to the surrounding culture, domain, or community, and that is novel enough to create change within that culture, domain, or community.

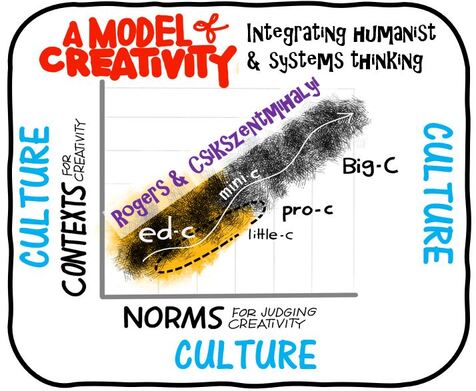

It seems to me that we have to accept both of these ways of thinking about creativity and work with both constructs when trying to make sense of it. In other words we are not dealing with either/or but both of these ways of thinking and we have to be able to accommodate both Rogerian and Csikszentmihalyian philosophies into our sense making in the manner depicted in Figure 1. This figure provides a graphical representation of the 4C model of creativity (4) and then adapts the model to include and educational domain (5).

These different ways of thinking about creativity are captured in the thinking and writings of 1) Carl Rogers who approaches creativity from a humanist, person- and individual- centred therapeutic perspective and 2) Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi who approaches creativity through the lens of individuals acting in systems and cultures. Kristen Bettencourt (3) neatly captures the philosophies of these thinkers and these notes are taken from her article.

Rogers (1) defines the creative process as “the emergence in action of a novel relational product, growing out of the uniqueness of the individual on the one hand, and the materials, events, people, or circumstances on the other” (p. 251). Rogers points out, “the very essence of the creative is its novelty, and hence we have no standard by which to judge it” (p.252). Rogers leaves room in the definition of creativity for the creator to define whether the expression is indeed novel, going as far to say that anyone other than the creator cannot be a valid or accurate judge. This is in contrast to Csikszentmihalyi’s emphasis on the creative expression serving to transform the culture or the domain.

Csikszentmihalyi (2) “creativity does not happen inside people’s heads, but in the interaction between a person’s thoughts and sociocultural context. It is a systemic rather than individual phenomenon” (2 p.23). Csikszentmihalyi tells us “To be human means to be creative,” he defines creativity as “to bring into existence something genuinely new that is valued enough to be added to the culture” (2 p.25), and “any act, idea, or product that changes an existing domain, or that transforms an existing domain into a new one” (2 p.28). The word “creative” is given to expression seen as novel in relation to the surrounding culture, domain, or community, and that is novel enough to create change within that culture, domain, or community.

It seems to me that we have to accept both of these ways of thinking about creativity and work with both constructs when trying to make sense of it. In other words we are not dealing with either/or but both of these ways of thinking and we have to be able to accommodate both Rogerian and Csikszentmihalyian philosophies into our sense making in the manner depicted in Figure 1. This figure provides a graphical representation of the 4C model of creativity (4) and then adapts the model to include and educational domain (5).

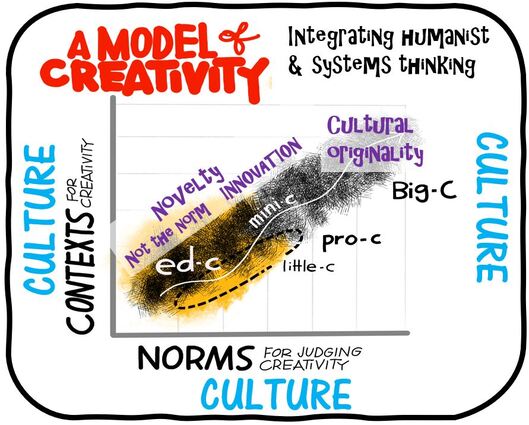

Another issue with creativity is the way we define it using terms like novelty and originality. The two are often used interchangeably but again we might use them in a more subtle way to locate creativity within these different ways of thinking about creativity. Using the 5C framework (Figure 2) we can show that in the little-c and ed-c part of the continuum are concerned with novelty and value that are defined and understood by individuals, or individuals and their immediate contacts – like family, friends teachers and peers. The appropriate concept of novelty in this context is the quality of being different, new, and unusual it is not the quality of being unique or original. As Carly Lassig (6) discovered in her grounded theory study of the creativity of adolescents, novelty is about behaving, performing and producing outside what is the accepted norm.

As we move along the continuum into the realm of expertise, for example in a work domain, novelty is often seen in the context of product innovation – the production of useful products that are, in some way, different to what existed before. Mostly these are incremental changes to things that already exists but sometimes they are original to a market. But novelty in the domain of expertise is also relevant to the production of new practices, performances, processes – for example bringing about change in an organisation. Novelty in this environment might occasionally be original at not only the level of individuals, but also organisations, markets or domains.

The most creative novel acts (Big-c) result in changes that affect one or more cultural domains and they are widely recognised for their originality by people who are highly knowledgeable and expert in their field.

Using this sort of reasoning I believe we can make better sense of creativity as a phenomenon by embracing this continuum of possibility.

Sources

1) Rogers, C. (1954). Toward a Theory of Creativity. ETC: A Review of General Semantics, 11, 249-260.

2) Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1996). Creativity: Flow and the Psychology of Discovery and Invention. New York: Harper Collins.

3) Bettencourt, K (2014) Rogers and Csikszentmihalyi on Creativity The Person Centered Journal, Vol. 21, No. 1-2, 2014 https://www.adpca.org/.../Bettencourt,%20Kristen%20(2014)%20

4) Kaufman, J and Behgetto R (2009) Beyond Big and Little: The Four C Model of Creativity Review of General Psychology Vol. 13, No. 1, 1–12

Available at: https://www.researchgate.net/.../228345133_Beyond_Big_and...

5) Jackson, N.J. and Lassig, C. (2020) Exploring and Extending the 4C Model of Creativity: Recognising the value of an ed-c contextual domain. Creative Academic Magazine CAM15 https://www.creativeacademic.uk/magazine.html

6) Lassig, C. J. (2012) Perceiving and pursuing novelty : a grounded theory of adolescent creativity. PhD thesis, Queensland University of

Technology. Available at: https://eprints.qut.edu.au/50661/

As we move along the continuum into the realm of expertise, for example in a work domain, novelty is often seen in the context of product innovation – the production of useful products that are, in some way, different to what existed before. Mostly these are incremental changes to things that already exists but sometimes they are original to a market. But novelty in the domain of expertise is also relevant to the production of new practices, performances, processes – for example bringing about change in an organisation. Novelty in this environment might occasionally be original at not only the level of individuals, but also organisations, markets or domains.

The most creative novel acts (Big-c) result in changes that affect one or more cultural domains and they are widely recognised for their originality by people who are highly knowledgeable and expert in their field.

Using this sort of reasoning I believe we can make better sense of creativity as a phenomenon by embracing this continuum of possibility.

Sources

1) Rogers, C. (1954). Toward a Theory of Creativity. ETC: A Review of General Semantics, 11, 249-260.

2) Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1996). Creativity: Flow and the Psychology of Discovery and Invention. New York: Harper Collins.

3) Bettencourt, K (2014) Rogers and Csikszentmihalyi on Creativity The Person Centered Journal, Vol. 21, No. 1-2, 2014 https://www.adpca.org/.../Bettencourt,%20Kristen%20(2014)%20

4) Kaufman, J and Behgetto R (2009) Beyond Big and Little: The Four C Model of Creativity Review of General Psychology Vol. 13, No. 1, 1–12

Available at: https://www.researchgate.net/.../228345133_Beyond_Big_and...

5) Jackson, N.J. and Lassig, C. (2020) Exploring and Extending the 4C Model of Creativity: Recognising the value of an ed-c contextual domain. Creative Academic Magazine CAM15 https://www.creativeacademic.uk/magazine.html

6) Lassig, C. J. (2012) Perceiving and pursuing novelty : a grounded theory of adolescent creativity. PhD thesis, Queensland University of

Technology. Available at: https://eprints.qut.edu.au/50661/

RSS Feed

RSS Feed