It is often said that necessity is the mother of invention and therefore the fundamental driver of our creativity but this is not the case when we play with and pursue ideas for the sheer joy of using our imagination and intellect. In such circumstances being creative is both personal - it gives us pleasure and a sense of fulfilment as we learn and create new meaning, and social - it gives us the sense that we are contributing to something bigger than ourselves that might be useful to others and outlive us when we are no more.

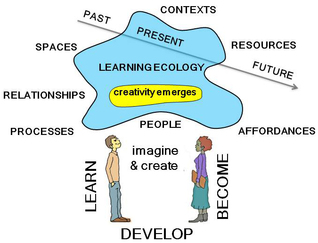

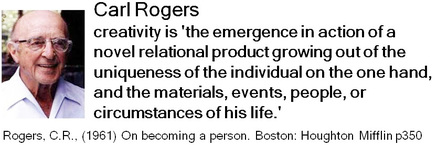

My involvement in trying to understand creativity preceded and influenced the way I engaged with and developed the idea of lifewide learning out of which grew the idea of learning ecologies (Jackson 2016). As the idea of a learning ecology grew (Figure) I began to see how our creativity must be involved in the process of learning, developing and achieving. So it is not surprising that as I have journeyed with the idea of creativity over the last fifteen years, I have come increasingly to appreciate and respect the way Carl Rogers framed the idea of personal creativity (Rogers 1961).

My involvement in trying to understand creativity preceded and influenced the way I engaged with and developed the idea of lifewide learning out of which grew the idea of learning ecologies (Jackson 2016). As the idea of a learning ecology grew (Figure) I began to see how our creativity must be involved in the process of learning, developing and achieving. So it is not surprising that as I have journeyed with the idea of creativity over the last fifteen years, I have come increasingly to appreciate and respect the way Carl Rogers framed the idea of personal creativity (Rogers 1961).

His view of personal creativity and how it emerges from the circumstances of our life, is an ecological concept. I like it as a way of framing our creativity because it affords us the most freedom and flexibility to explore and appreciate the ways in which we and our purposes are connected to our experiences and the physical, social and psychological worlds we inhabit.

But the idea that creativity and the experience of being creative involves people acting and interacting with their world can, like so many ideas in learning and education, be seen in the ideas and writings of John Dewey (Dewey 1934). Glavenau et al (2013) provide a description of Dewey's model of human experience. 'Action starts... with an impulsion and is directed toward fulfilment. In order for action to constitute experience though, obstacles or constraints are needed. Faced with these challenges, the person experiences emotion and gains awareness (of self, of the aim, and path of action). Most importantly, action is structured as a continuous cycle of “doing” (actions directed at the environment) and undergoing” (taking in the reaction of the environment). Undergoing always precedes doing and, at the same time, is continued by it. It is through these interconnected processes that action can be taken forward and become a “full” experience (Glavenau et al 2013:2).

These ideas were developed by Woodman and Schoenfeldt (1990) who proposed an interactionist model of creative behavior at the individual level. This model was later developed by Woodeman et al (1993) to embrace the organisational social-cultural context. The interactionist model, is an ecological model of creativity. Creativity is viewed as the complex product of a person's or persons' behavior(s) in a given situation. The situation is characterized in terms of the contextual and social influences that either facilitate or inhibit creative accomplishment. The person is influenced by various antecedent conditions ie that immediately precede and influence thinking and action, and each person or persons has the potential to draw on all their qualities, values, dispositions and capabilities (ie everything they are, know and can do and are willing to do) to engage with the situation.

Meusburger (2009a, b) also emphasises the significance of places, environments and spatial contexts in personal creativity and draws attention to the way in which creative individuals seek out environments that enable their creativity to flourish. People who are driven to be creative seek and find favourable environments to be creative in. They also modify existing environments in ways that enable them to realise their creativity and they also create entirely new environments (eg an ecology for learning) in which they and others can be creative. They are able to see the affordance in an environment they inhabit and use it to realise their creative potential.

The interactionsist ways of looking at creativity is consistent with the ideas of 'creativity as action and of creative work as activity' (Glavenau et al 2013:1 & 11). 'In contrast to purely cognitive models, action theories of creativity start from a different epistemological premise, that of interaction and interdependence. Human action comprises and articulates both an “internal” and “external” dynamic and, within its psychological expression, it integrates cognitive, emotional, volitional, and motivational aspects. Creativity, from this stand-point, is in action as part and parcel of every act we perform6. Creativity exists on the other hand also as action whenever the attribute of being creative actually comes to define the form of expression' (Glavenau et al 2013:2). We might anticipate that there is no clear boundary separating creative work and work that is essentially not conceived, defined or presented as being creative but which results in smaller or larger acts of creativity and leads to the emergence and formation of new ideas or things. In other words there must be a continuum of activity that is essentially creative to activity that is essentially not creative. Probably a lot of the work done by people whose work is not categorized as being creative is of this type. The model of an ecology for learning, development and achievement shown in Figures 1 and 2, is an interactionist model : people interacting with their environment and the people and things in their environment.

But the idea that creativity and the experience of being creative involves people acting and interacting with their world can, like so many ideas in learning and education, be seen in the ideas and writings of John Dewey (Dewey 1934). Glavenau et al (2013) provide a description of Dewey's model of human experience. 'Action starts... with an impulsion and is directed toward fulfilment. In order for action to constitute experience though, obstacles or constraints are needed. Faced with these challenges, the person experiences emotion and gains awareness (of self, of the aim, and path of action). Most importantly, action is structured as a continuous cycle of “doing” (actions directed at the environment) and undergoing” (taking in the reaction of the environment). Undergoing always precedes doing and, at the same time, is continued by it. It is through these interconnected processes that action can be taken forward and become a “full” experience (Glavenau et al 2013:2).

These ideas were developed by Woodman and Schoenfeldt (1990) who proposed an interactionist model of creative behavior at the individual level. This model was later developed by Woodeman et al (1993) to embrace the organisational social-cultural context. The interactionist model, is an ecological model of creativity. Creativity is viewed as the complex product of a person's or persons' behavior(s) in a given situation. The situation is characterized in terms of the contextual and social influences that either facilitate or inhibit creative accomplishment. The person is influenced by various antecedent conditions ie that immediately precede and influence thinking and action, and each person or persons has the potential to draw on all their qualities, values, dispositions and capabilities (ie everything they are, know and can do and are willing to do) to engage with the situation.

Meusburger (2009a, b) also emphasises the significance of places, environments and spatial contexts in personal creativity and draws attention to the way in which creative individuals seek out environments that enable their creativity to flourish. People who are driven to be creative seek and find favourable environments to be creative in. They also modify existing environments in ways that enable them to realise their creativity and they also create entirely new environments (eg an ecology for learning) in which they and others can be creative. They are able to see the affordance in an environment they inhabit and use it to realise their creative potential.

The interactionsist ways of looking at creativity is consistent with the ideas of 'creativity as action and of creative work as activity' (Glavenau et al 2013:1 & 11). 'In contrast to purely cognitive models, action theories of creativity start from a different epistemological premise, that of interaction and interdependence. Human action comprises and articulates both an “internal” and “external” dynamic and, within its psychological expression, it integrates cognitive, emotional, volitional, and motivational aspects. Creativity, from this stand-point, is in action as part and parcel of every act we perform6. Creativity exists on the other hand also as action whenever the attribute of being creative actually comes to define the form of expression' (Glavenau et al 2013:2). We might anticipate that there is no clear boundary separating creative work and work that is essentially not conceived, defined or presented as being creative but which results in smaller or larger acts of creativity and leads to the emergence and formation of new ideas or things. In other words there must be a continuum of activity that is essentially creative to activity that is essentially not creative. Probably a lot of the work done by people whose work is not categorized as being creative is of this type. The model of an ecology for learning, development and achievement shown in Figures 1 and 2, is an interactionist model : people interacting with their environment and the people and things in their environment.

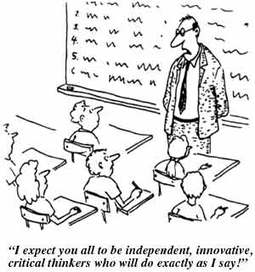

From an educational perspective these are exciting and challenging ideas. Necessarily they must involve the teacher and her students interacting with each other, the multiplicity of knowledges they are using and their physical, virtual and psychological environments. It is more than simply pedagogy, although pedagogy is a major contributor to an ecology in which creativity can flourish. It involves the individual and collective imaginations and actions of everyone in the learning ecology.

As a first step in our exploration of these ideas, in July members of the Creative Academic community came together in a conversation on the #creativeHE platform to consider the idea of creative ecologies and co-create new meanings as ideas were combined and new understandings were gained. The September issue of Creative Academic Magazine (CAM5) is inspired by this conversation and draws much of its content from the ideas and perspectives that were shared. The next step will be to build an ecology for collaborative inquiry so that these ideas can be explored further. Further details of this project will be published in October and we welcome your involvement.

Sources

Dewey, J. (1934). Art as Experience. NewYork: Penguin.

Glaveanu V., Lubart T, Bonnardel, N., Botella, M., Biaisi, P-M., Desainte-Catherine M., Georgsdottir, A., Guillou, K., Kurtag,G., Mouchiroud, C., Storme, M., Wojtczuk, A., and Zenasni , F. (2013) Creativity as action: findings from five creative domains Frontiers in Psychology Volume 4 | Article 176 1-14 available at: http://journal.frontiersin.org/article/10.3389/fpsyg.2013.00176/full

Jackson N J (2016a) Exploring Learning Ecologies http://www.lulu.com/home

Meusburger, P. (2009) Milieus of Creativity: The Role of Places, Environments and Spatial Contexts,

in Meusburger, P., Funke, J., and Wunder, E. (eds.), Milieus of Creativity: An Interdisciplinary Approach to Spatiality of Creativity. Knowledge and Space 2. Springer 97-149

Meusburger, P., Funke, J., and Wunder, E. (eds.) (2009) Introduction: The Spatiality of Creativity in Meusburger, P., Funke, J., and Wunder, E. (eds.), Milieus of Creativity: An Interdisciplinary Approach to Spatiality of Creativity. Knowledge and Space 2. Springer 1-10 available at:

Rogers, C.R., (1961) On becoming a person. Boston: Houghton Mifflin

Woodman, R. W. and Schoenfeldt, L. F. (1990) An interactionist model of creative behaviour. J. Creat. Behav, 24, 279-290

Woodman, R.E., Sawyer J. E. and Griffin, R.W. (1993) Toward a Theory of Organizational Creativity The Academy of Management Review, Vol. 18, No. 2. (Apr., 1993), 293-321, available at:

file:///C:/Users/norman/Documents/AAAAA/Documents%20(4)/CREATIVE%20ECOLOGY/reference%20to%20Woodmans%20interactionist%20model.pdf

Norman Jackson

Commissioning Editor Creative Academic Magazine

As a first step in our exploration of these ideas, in July members of the Creative Academic community came together in a conversation on the #creativeHE platform to consider the idea of creative ecologies and co-create new meanings as ideas were combined and new understandings were gained. The September issue of Creative Academic Magazine (CAM5) is inspired by this conversation and draws much of its content from the ideas and perspectives that were shared. The next step will be to build an ecology for collaborative inquiry so that these ideas can be explored further. Further details of this project will be published in October and we welcome your involvement.

Sources

Dewey, J. (1934). Art as Experience. NewYork: Penguin.

Glaveanu V., Lubart T, Bonnardel, N., Botella, M., Biaisi, P-M., Desainte-Catherine M., Georgsdottir, A., Guillou, K., Kurtag,G., Mouchiroud, C., Storme, M., Wojtczuk, A., and Zenasni , F. (2013) Creativity as action: findings from five creative domains Frontiers in Psychology Volume 4 | Article 176 1-14 available at: http://journal.frontiersin.org/article/10.3389/fpsyg.2013.00176/full

Jackson N J (2016a) Exploring Learning Ecologies http://www.lulu.com/home

Meusburger, P. (2009) Milieus of Creativity: The Role of Places, Environments and Spatial Contexts,

in Meusburger, P., Funke, J., and Wunder, E. (eds.), Milieus of Creativity: An Interdisciplinary Approach to Spatiality of Creativity. Knowledge and Space 2. Springer 97-149

Meusburger, P., Funke, J., and Wunder, E. (eds.) (2009) Introduction: The Spatiality of Creativity in Meusburger, P., Funke, J., and Wunder, E. (eds.), Milieus of Creativity: An Interdisciplinary Approach to Spatiality of Creativity. Knowledge and Space 2. Springer 1-10 available at:

Rogers, C.R., (1961) On becoming a person. Boston: Houghton Mifflin

Woodman, R. W. and Schoenfeldt, L. F. (1990) An interactionist model of creative behaviour. J. Creat. Behav, 24, 279-290

Woodman, R.E., Sawyer J. E. and Griffin, R.W. (1993) Toward a Theory of Organizational Creativity The Academy of Management Review, Vol. 18, No. 2. (Apr., 1993), 293-321, available at:

file:///C:/Users/norman/Documents/AAAAA/Documents%20(4)/CREATIVE%20ECOLOGY/reference%20to%20Woodmans%20interactionist%20model.pdf

Norman Jackson

Commissioning Editor Creative Academic Magazine

RSS Feed

RSS Feed