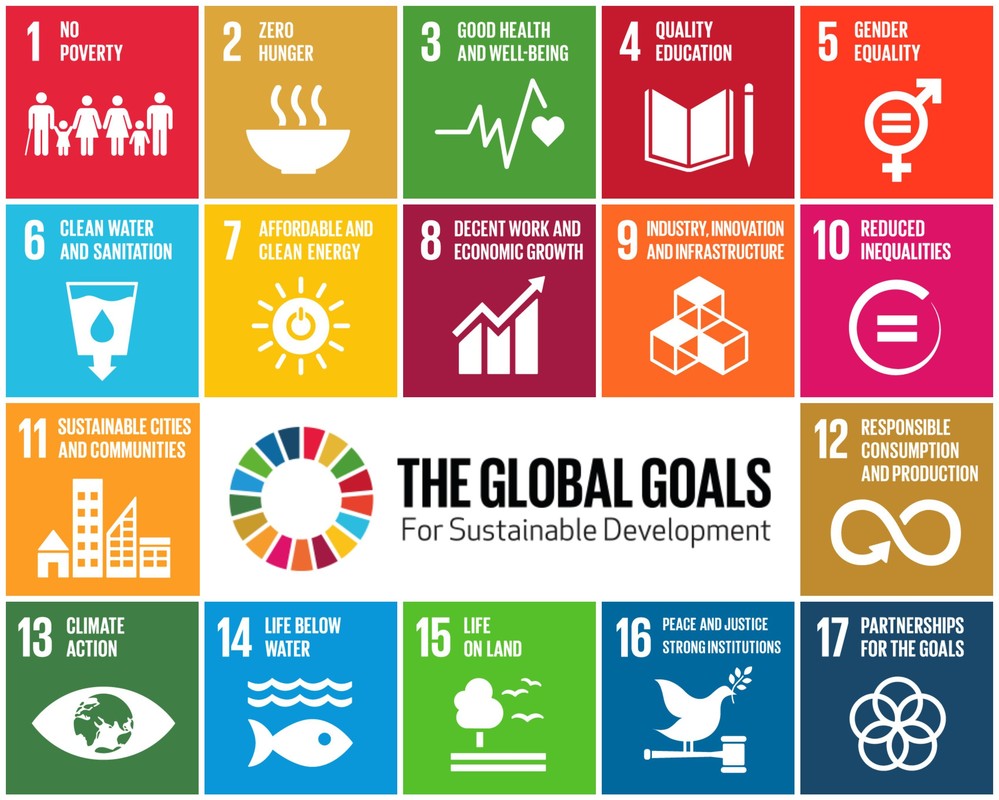

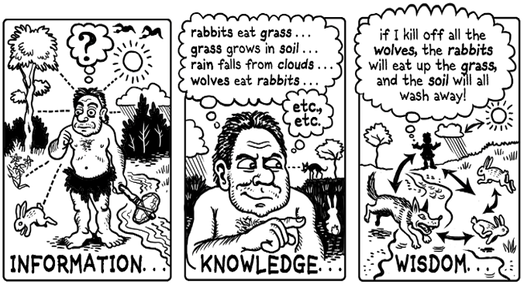

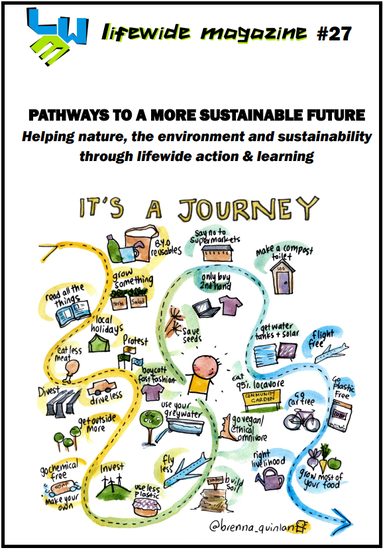

Imagination and creativity are at the heart of the generative capacity of humans and we must be expansive in our vision of what our imagination and creativity are for. We should recognise that what teachers are doing to encourage the creative development of learners, and each other, is also helping to build capacity and potential for a more sustainable regenerative future. After all, it is the current generation of higher education learners that will have to repair the world that previous generations have messed up!

So its great that teachers are willing to share their stories about how they are encouraging creativity in themselves and their students and in the latest issue of Creative Academic Magazine we include ten stories of creative teaching and learning selected from the “Annual #creativeHE Collection” e-book7 edited by Nathalie Tasler, Rachelle O’Brien and Alex Spiers. The editors have done a wonderful job in stimulating interest in the #creativeHE academic community, drawing together 30 diverse contributions from 60 authors, educators and students, from the United Kingdom, Slovenia, Nigeria, Canada, Italy and Germany. Their contributions capture creative and resourceful practices during the pandemic that show the authors’ determination to create stimulating environments for learning in spite of the restrictions brought about by the pandemic.

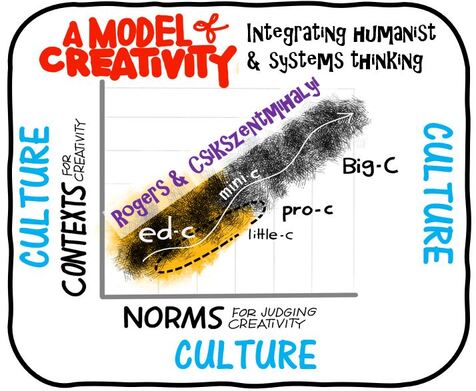

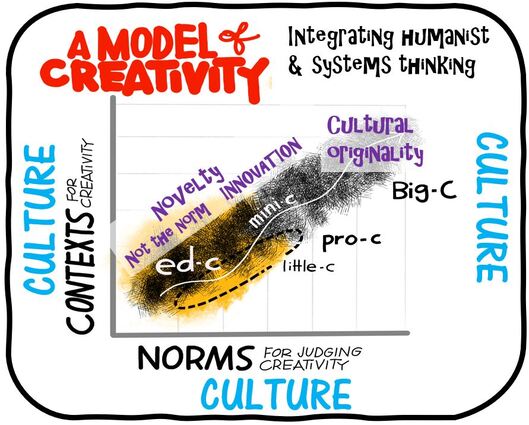

The issue also includes an interesting article by Hansika Kapoor and James Kaufman, who explore creativity in the pandemic using the interpretive framework based on the Four C model of creativity8 . This enables us to appreciate the bigger social, environmental and cultural dynamic within which higher education teachers make their own distinctive professional contributions. And not to miss an opportunity, I have once again called for an educational (ed-c) domain within which the important role of education in encouraging and facilitating the creative development of people, can be recognised.

READ CAM 20

RSS Feed

RSS Feed